In this lesson I will drone on about musical drones (and the concept of pedal tones). This is a simple concept that can lead to some wonderful complexity. Paradoxically, by focusing on sustaining just a single note, we’ll open the door to advanced harmonic principles that venture beyond that common major or minor key. For more examples and explanations, be sure to watch the video above.

A drone is a sustained note (or notes) that keeps going through an entire section. There are entire genres built around this concept, specifically Carnatic and Hindustani music from India. The tanpura gets tuned to a root and fifth, creating this warm drone sound that performers can improvise over using all kinds of scales.

This technique wasn’t popular in the Western world until the 1960s when the Beatles started taking trips, some of which were to India. “Tomorrow Never Knows,” which opens with a sitar drone and blares away until the end on the note C, is one of the earliest examples I can find where drones were an important element to a western pop song. The Beatles again employ this technique in “Blue Jay Way,” which drones a C note throughout.

The Mind-Altering Effect Of Drones

Drone music can be flat out trippy. It taps into a more reflective, trance-like state; you’ll frequently hear it in meditation music, “healing tones,” and ambient tracks. There’s something about that static, unchanging note that just puts our brain in a different space or state of focus.

If you’re trying to write something otherworldly or meditative, drones are certainly worth employing to harness this effect. If, say, you need to write a long section of a song that is meant to be ethereally contemplative, then utilizing a long drone would probably help you achieve that mood.

However, as we’ll now see, musical drones don’t always have to sound so psychedelic!

A Drone Is A Blank Canvas

When you’re asked to write melodies, or play solos, over a chord or progression, your options are limited. You can’t just play any old scale over any old chord and expect it to work. But when the underlying music is just a single droning note, you have infinitely more scales to choose from. Your choice of scale can recolor the music into many different shades.

To demonstrate, here’s a jam I wrote using only the note A. Atop it, I cycle through several different scales. Listen to how each scale changes the color, or mood, of the surrounding music. (To know which scale I’m playing, and when, make sure to watch the video posted at the top – it’s all shown on screen there)

- A Phyrgian Dominant

- A Major

- A Blues

- A Hungarian Minor

- A Mixolydian

- A Lydian Dominant

- A Whole Tone

Not sure what those scales mean, or how you’d even approach them? Then you should consider studying through my book, The Chord Progression Codex. It’s a deep dive into chord progressions and “vertical harmony,” and goes into detail behind which scales are used over which chords (and why!). It’s a perfect companion guide to learn theory or simply have as a robust reference.

Modern Acoustic Guitar Drones

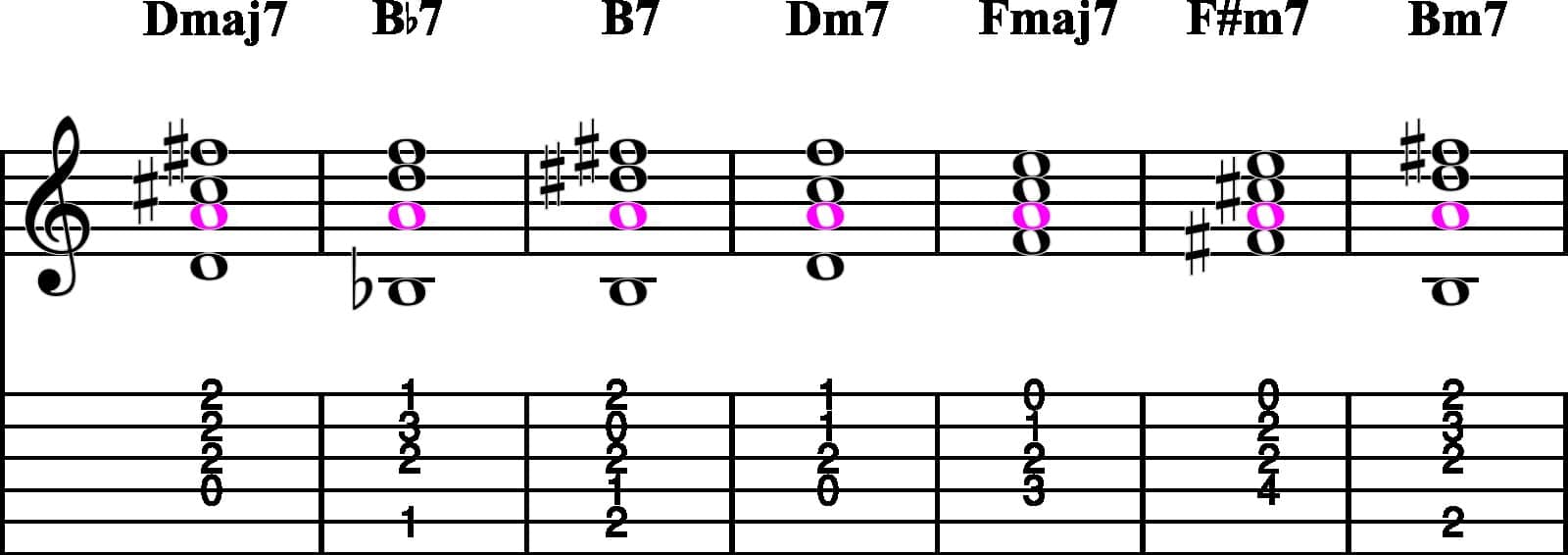

Guitarists use drones all the time, perhaps without even realizing it. When we play an E major chord, the open E and B strings naturally ring out. We can then play different partial barre chord shapes while letting those strings drone, creating a nice shimmery and light chord movement.

For example, we can start with a simple I – V – vi – IV in E, which is E – B – C#m, and A. Then instead of fretting those entire chords, we’ll only fret the lowest notes of them while allowing strings 1 and 2 to ring open, using the following chord shapes. The end result is a chord progression that is much richer, while also being easier to play.

Though the chord labels are now more complex, we should recognize that the actual chords themselves are just a natural byproduct of the guitar’s geometry. These are easy chords to stumble upon, whether you know their formal names or not.

Pedal Tones

“Pedal tones” refer to pretty much the same thing as drones, but this phrase is usually reserved for shorter moments of droning (and not entire sections or songs) that occurs on the bass voice. The verse section in Pink Floyd’s “Us and Them,” for example, pedals several chords over a D note.

“Eye of the Tiger” by Survivor also contains a verse section with several chords pedaled over a single C note.

The difference the pedal tone makes in these examples is significant. Compare those smooth, floating chord changes that employ pedal tones to the same progression without the pedal. Here’s an original example to highlight the difference; this electronically produced progression goes D – Ab – G – F, and you can hear the bass play each of those root notes as each chord is voiced:

Now let’s hear that same chord progression, but we’ll simply keep D as a bass pedal tone the whole time. This has an unmistakable effect on the progression; you should aim to get familiar with that effect, so you can employ it when you feel it’s needed.

These examples all explore a bass pedal tone, but the concept can apply to other notes in the harmony as well.

Composing with Pedal Tones

Try this exercise – pick a single note and ask yourself what triads contain that note. For example – what triads contain A? Well, you’ve got A major and A minor (A as the root), F# minor and F major (A as the third), D major and D minor (A as the fifth). String these together in some order and even though they have no relationship to each other except that common A note, they’ll sound connected in some way.

Expand this even further, and ask yourself what sorts of 7th chords include A? Or 9th chords? You’ll find a plethora of options to choose from, each providing a tether to the note A. Writing chord movements like this (in search of a common tone) is a guaranteed way to stretch harmony beyond the confines of regular major or minor keys.

Here’s an example from Chapter 17 of The Chord Progression Codex, which explores this concept in more detail. As you can see and hear, each of these chords contains the note A, keeping the entire movement cohesive. Despite that, the progression itself is “chaotic” in the sense that it has no clear tonal center or home base.

To Summarize

Casting theory aside, here’s what you should take away from this lesson.

By intentionally composing chord movements that include a common tone (aka a pedal tone or a drone note), we can modify the feeling and mood of the initial progression. Droning on the bass note has a certain effect, droning on a high melody can have another, and of course there’s a middle ground between those. If you’ve written a chord progression and are trying to enhance it, consider finding a single note to sustain through two or more chords. This will often create a more complex chord label without sounding super complicated.

If you enjoyed this lesson, consider checking out my Music Theory and Songwriting Course to learn all of the important skills that modern songwriters should know. Or, as mentioned earlier, the Chord Progression Codex, if you’d like to understand harmony better.