Ever wonder how Boston, The Allman Brothers, Iron Maiden, and The Eagles wrote harmonized guitar parts? Or why Simon and Garfunkel sing the notes they do in songs like “Sounds of Silence?”

This video is an extensive demonstration of that process and all of the considerations one might take when trying to write harmony lines such as those. Below is a very basic summary of the concepts inside.

Harmonized Thirds

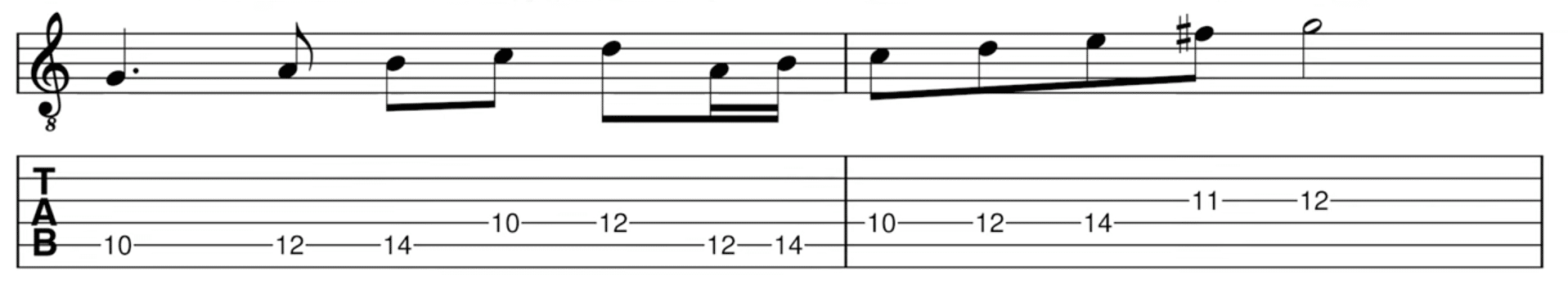

Here’s a simple melodic line in the key of G. It goes up the scale a bit, then jumps back down and ascends again.

A simple way to harmonize above this is with diatonic thirds, which you can think of as skipping over the next note of the scale. Here are the notes of the G scale, written in order. We can harmonize the first note, G, with the third note, B. Similarly, we can harmonize note 2 (A) with note 4 (C).

If we harmonize each note of our original lick this way, we’ll end up with the following:

Sixths

(At this point, things might get murky if you don’t know your formal intervals. I recommend you read the 2nd chapter of the Chord Progression Codex (for free!) to learn them.)

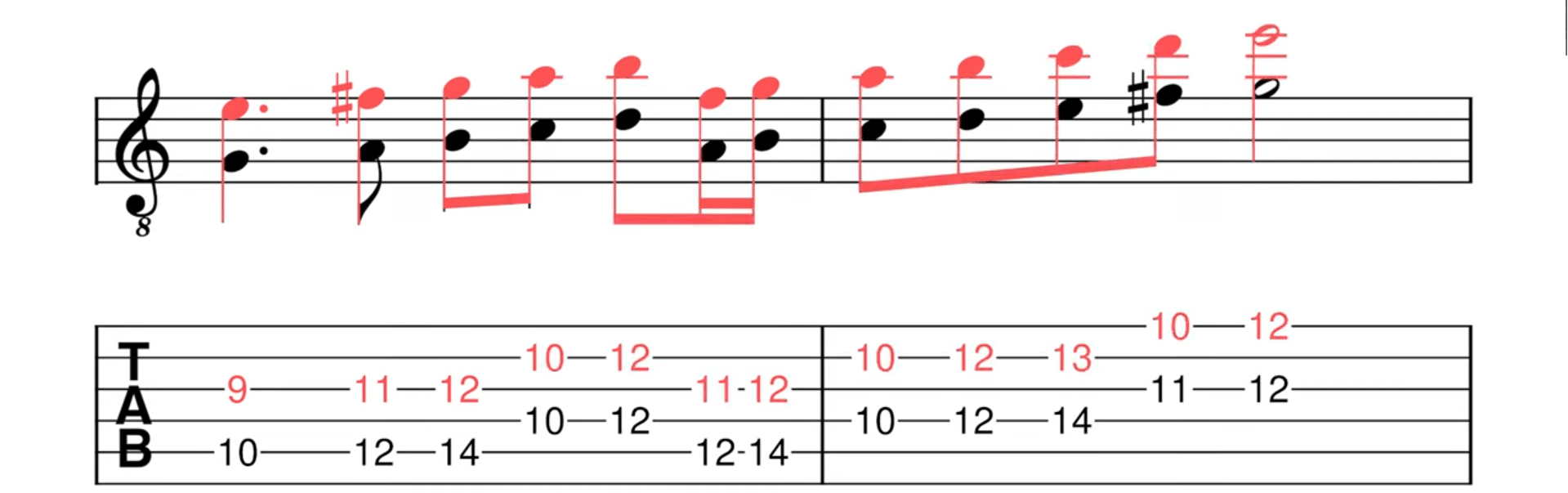

Let’s take that harmony line that we wrote, which is a diatonic third above our original melody, and move it down an entire octave.

If you calculate the distances between these notes, you’ll see that they’re actually sixths – not thirds. This is because thirds and sixths are complements of each other. When you invert a third, you end up with a sixth, and vice versa.

It’s important to remember when you’re writing a harmony line that your melody line may not always want what ever is up a third! For example, if your original melody is voicing the 5th of a chord, then adding a 3rd above it will introduce some type of 7th quality to the overall sound that may not be desired.

However, if your melody is voicing the 3rd of a chord, then harmonizing with it up a 6th will end up summoning the root note of the underlying chord. This is why you want to experiment with diatonic sixths just as eagerly as you would thirds.

Fourths and Fifths

These two intervals are again complements of one another. If a third or sixth doesn’t sound good above or beneath your original melody, try one of these instead.

There is a famous “rule” that you should not harmonize with parallel fifths. That restriction does not apply whatsoever to modern rock genres and can be safely ignored until you decide to learn counterpoint and similar classical theory.

Use ’em all!

When writing a harmony line, I like to include combinations of everything we’ve discussed here. I also pay close attention to the motion of my harmony: are the two voices moving in parallel with one another? Or are they in contrary motion? Or oblique motion?

Those are all concepts I cover in my other harmony lesson, found here.

Learn More

If you enjoy my lessons or want to learn more about music theory from the ground up, you’ll love my Music Theory and Songwriting Course. It’s a complete guide writing, understanding, and creating modern music on any instrument.