In 1971, John Lennon released “Imagine,” a song that became both a commercial and artistic success. At its core, this song features what I consider to be a simple but perfect chord progression. Let’s examine every chord in this composition and explore how simple musical concepts can create something truly special. We’ll also analyze how arrangement techniques help add to the overall mood and vibe of this song.

The Value of Inverted Chords

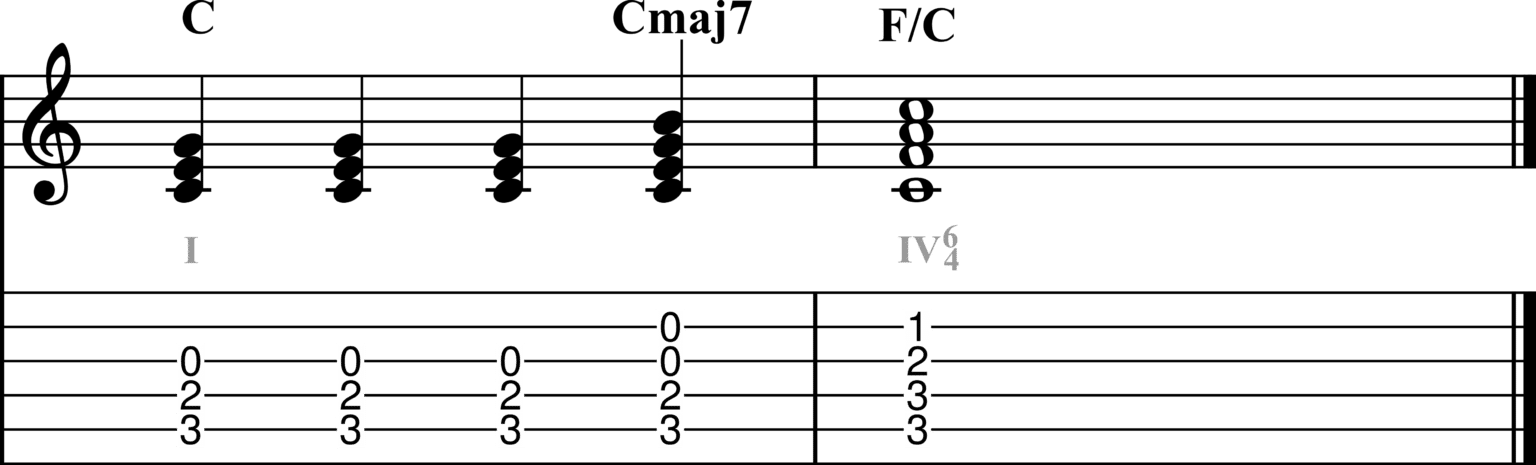

To understand what makes “Imagine” work so well, we need to start with a basic comparison. Let’s look at a standard I-IV progression in C major: C major to F major. When you play these chords in root position, you get a bold, direct change – the bass note jumps from C to F, creating a clear, cut-and-dry chord movement.

Now let’s try the same progression with one crucial difference: we’ll play that IV chord in second inversion, which means its fifth will now be its lowest note (we can call this F/C or F64). This keeps C in the bass for both chords, making the progression feel completely different – smoother, less confrontational, more mellow.

This technique is called a pedal tone – when a bass note stays the same across different chords. That constant C in the bass acts like a tether to home base, making the chord changes feel less dramatic and more flowing.

Major Seventh Tonic Chord

The actual pattern that Lennon plays here involves three beats of a simple C triad (C-E-G), and then a fourth beat of a Cmaj7 chord where a high B note is added. Cmaj7 is a dreamy and soft alternative to the cheery and straightforward C major chord, and its presence for only a single beat creates an ephemeral dreaminess. This example comes from my book, The Chord Progression Codex, which teaches modern harmony and chord progressions.

In major keys, you should expect to see the tonic chord voiced as a maj7 chord instead. Especially in jazz songs, or styles meant to evoke a warm or relaxed feeling.

Melody In The Chords

Observe the chord progression from above and focus on the highest notes in each chord. They trace out the following movement:

- C major: G (top note)

- Cmaj7: B

- F/C: A

That melody line – G, B, A – is exactly what Lennon sings: “Imagine there’s no heaven.” The vocal melody isn’t separate from the chords; it’s built right into the chord progression itself.

Chromatic Touch (Passing Tones)

After the F/C chord, and before repeating back to C, we get a small but distinctive chromatic run. The natural 6th note (A) moves up to the augmented 6th (A#), then to the natural 7th (B). This ascending chromatic line seems like it should resolve up to C, but instead drops down to G.

This quirky little chromatic movement might be the most distinctive element of the entire verse riff. Imaj7 to IV74 isn’t that unique, but these chromatic passing tones certainly are. In addition, that unexpected downward resolution gives the progression a unique character.

Arrangement

The specific voicings Lennon chose are crucial to the song’s dreamy quality. For the C major chord, he uses a simple root position triad (C-E-G) with G on top. For the F/C chord, he plays a tight, compact voicing (C-F-A) in a relatively low register.

High notes tend to sound brighter and happier, while lower notes create a foggier, hazier vibe. By keeping these chords in that lower, muddier register, Lennon perfectly captures the daydreaming feeling that the song title suggests.

Double-Tracked Pianos

Here’s a production detail that’s often overlooked: the piano was recorded twice, with one performance panned left and another panned right. These aren’t identical performances – there are small discrepancies between them.

This creates an inconsistent but effective result. Sometimes over that C triad, you hear a D note (making it a C add 9), sometimes you don’t. One piano might be playing rhythms that the other isn’t. Though double tracking is quite popular, this “random sloppiness” isn’t a commonly desired effect. In this case, those little discrepancies create a natural chorus effect that seems to enhance the dreamy, hazy quality of the song.

The Pre-Chorus: Walking Bass Line

The arrival of the chorus brings fresh new diatonic chords to the table. We’re in the key of C, which contains the following triads, only two of which we’ve seen so far:

Now, we’ll see the vi chord (Am) and the ii chord (Dm) appear as part of the following pre-chorus movement:

Notice how the bass voice descends stepwise through the C scale, starting on F and moving down through E, D, and then C. Then, the bass jumps to G, the dominant, for a clear and obvious authentic cadence to return us to our tonic chord, and repeat the verse.

This creates an interesting contrast with the verse. In the verse, the bass stayed constant while the upper voices changed. Here, it’s the opposite – the upper voices stay relatively stable while the bass moves underneath. You can see this by comparing the high notes of F (F-A-C) to those of Am (A-C-E) and Dm7 (D-F-A-C).

The Chorus “III7 chord”

Here’s the final progression this song offers us to analyze:

That E7 major chord deserves special mention. In the key of C major, an E major triad (which is found within E7) is out of key. Music students should recognize that E7 is a secondary dominant chord – it naturally pulls our ear towards Am, the vi chord in this key.

However in this case, we can see it’s instead pulling our ear up a half-step to arrive at F. We can call this type of movement a chromatic approach – every single note of F is being arrived at from a half-step below.

If this E7 chord was moving to Am like it’s “supposed to do,” then we’d give it the numeral V7/vi, which means “the dominant chord of the sixth triad” and would be pronounced “five of six.” In this case, since it’s not really behaving like a secondary dominant, I personally think it’s fine to give the numeral a label of III7 instead.

Just note that this specific chord, III7 or V7/vi, has two very popular destinations: the vi and the IV.

The Beauty of Simplicity

What makes John Lennon brilliant is what he does with simple materials. This entire song is built from basic C major scale chords with just a touch of chromatic interest and one secondary dominant. The magic is in the choices:

- When to use inversions versus root position chords

- Where to place pedal tones

- How to voice chords for maximum emotional impact

- The decision to double-track the piano (even imperfectly)

I say this in lots of my videos, and I believe it: it’s not about what you write, it’s about what you do with what you write. Lennon took the most basic chord progression possible and, through careful attention to voicing, inversion, production choices, and melodic integration, created something that sounds unique and original.

The lesson here is that sophisticated songwriting doesn’t require sophisticated chord progressions. Sometimes the most powerful music comes from taking simple ideas and executing them with precision, taste, and a clear vision of the emotional effect you want to create. If you enjoyed this post and want to learn more about chord theory, you should get my book The Chord Progression Codex. It’s a complete guide to modern harmony like we’re discussing here, and serves as a wonderful reference for advanced musicians as well.

Or, if you’d like to learn more about music besides just harmony and chords, check out my complete Music Theory and Songwriting Course to understand all the elements needed for modern composing.