For the longest time, I thought songwriting was one of those mysterious talents you’re either born with or you’re not. I was convinced I fell into the “not” category. Learning songs was hard enough—writing them seemed impossible.

Then I discovered diatonic chords and learned how to use them properly. This simple concept changed everything for me, and by the end of this post, you’ll be able to write chord progressions that sound wonderful and actually work.

To assist in this lesson, I’ll be using several audio and visual examples taken directly from The Chord Progression Codex.

The Importance of Diatonic Chords

We’re going to focus on major keys today, which covers about 60-70% of Western music. Even if you’re already familiar with diatonic chords, stick with me – I’m going to put some helpful restrictions on our playing that will actually make better-sounding progressions easier to create.

Building Your Foundation: The C Major Scale

Let’s start with C major since it’s the simplest. Starting on C, we use this formula of whole steps and half steps. In case you don’t know, a halfstep is when you travel from one note right up to the next one (like from a white key up to the next black key), or on a guitar it’s when you move up a single fret. A whole step is just two notes or frets.

Whole-Whole-Half-Whole-Whole-Whole-Half

This gives us the notes: C – D – E – F – G – A – B – C

In music theory, we assign each note a Roman numeral:

Each of these notes will assigned their very own chord. Some notes, like C, F, and G will get major chords. However, notes D, E, and A will get minor chords, and have their roman numeral changed to lowercase.

The last note, B, gets a special kind of triad called “diminished,” which uses a lowercase numeral and a º sign.

Putting this all together, we can now see all seven chords that exist in the key of C. Pay special attention to the numeral formula – it’s the most important thing you can possibly memorize early on in your songwriting studies.

These seven chords are literally all you need to launch a career. For today’s lesson though, we’re going to focus on six of them, and completely ignore that diminished chord. It’s a wonderful topic to learn, but a bit’s advanced for beginners.

Now that we can build the diatonic triads of C, let’s find out what we can do with them to write music.

Three Simple Rules for Progressions

To write your first chord progressions, I want you to follow these three rules:

Rule 1: Write Four Measures

Four measures is a perfect starting point. Many sections in popular music will repeat a 4-measure loop.

Rule 2: Start on the I Chord

Always begin your progression on the I chord, which is also called the tonic. Since we’re working in the key of C, that means we need to start on a C chord. This establishes your key clearly to the listeners ear.

Rule 3: End on IV or V

Your last measure should be either F major (IV) or G major (V). Both of these chords have a tendency to pull us back to the tonic chord, helping create a natural and seamless loop to repeat.

With just these rules, you can literally guess at anything in between and get a great-sounding chord progression.

Let’s Write Some Progressions

Let’s put this to work. We have a “starter template” for a chord progression, now all we need to do is fill in those middle measures. We can choose any diatonic chord from our scale that we learned earlier (but remember to avoid the B diminished chord for now!).

For example, for measure 2 I’ll place in the iii chord (Em), then follow it up with the ii chord (Dm) to create this progression. The last measure needs to be IV or V (F or G), and I’ll opt for F this time:

That sounds pretty nice! Now let’s try the same progression but end with V instead:

Notice how ending on G gives you a brighter, bolder sound? That’s the difference between the two cadences:

- IV to I (F to C) = Plagal Cadence. Feels like soft landing to the tonic chord.

- V to I (G to C) = Authentic Cadence. Feels like a strong strong, decisive arrival to the tonic.

Both work beautifully and create that infinite loop feeling that makes you want to repeat the progression. Atop this progression you write other parts that use notes from the C scale: vocal melodies, guitar lines, flutes, whatever floats your musical boat.

Another Quick Example

Let’s try something different. Starting on C again, I’ll go to the vi chord (A minor), then V (G major), then stay on V for the last measure:

Remember, there’s no rule against using the same chord twice in a row. You can literally pick any numbers between 1 and 6 for the middle measures, and as long as you follow the three rules, it will work.

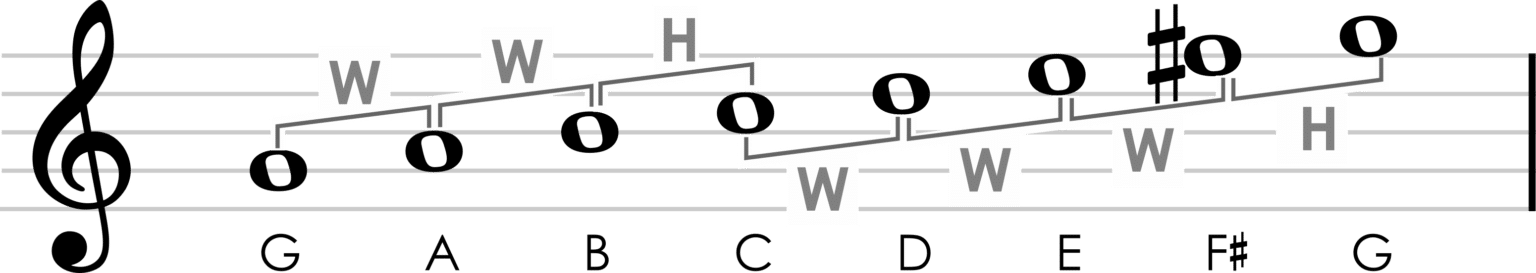

Expanding to Other Keys: G Major Example

To make sure you really grasp this concept, let’s quickly do the same thing in G major. Starting on G, I’ll build the scale using the same whole-step/half-step pattern:

Next, let’s apply the exact same Roman numerals that we saw before:

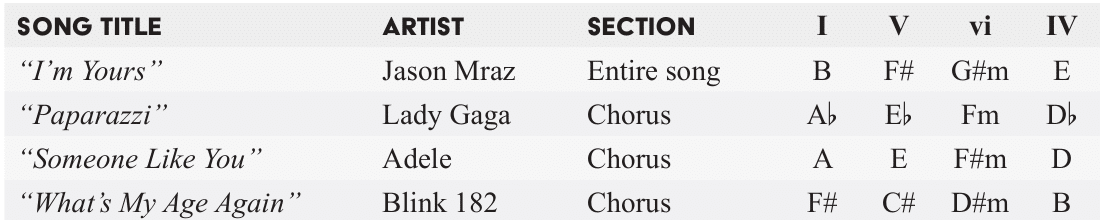

Let’s create the world’s most popular 4-chord loop, this time in G major. It looks and sounds something like this:

This progression has been used in countless songs over the past decades, and it won’t let up any time soon. Here’s a few places you may have heard it:

Beyond the Basics

These rules are intentionally limiting, and that’s the point. You don’t want to write soulful, emotional music with rigid rules forever. But this is an excellent starting place for getting something that actually sounds musical.

The Reality of Songwriting

In a perfect world, you’d sit down with your instrument and emotions would just pour out. But you can’t count on that. When inspiration doesn’t strike, you need to brute force your way through and write something, anything, to get the creative process moving.

For me personally, maybe 5% of my songwriting is that effortless, magical process. The other 95% is methodically working through ideas, using techniques like this, until something clicks and the real inspiration takes over.

Your Next Steps

Start simple: write a progression in a different key every day. Try E major tomorrow, F major the next day, F# the day after. Get familiar with how each key feels on your instrument.

If you’re into electronic music, try programming these chord progressions as strings or synthesizers. The important thing is to practice by actually writing and using these concepts.

Going Further

When you’re ready to expand beyond these six chords, explore:

- Secondary dominant chords – chords outside your key that lead to chords within your key

- Borrowed chords – chords from parallel modes

- Key changes – you don’t have to stay in one key for an entire song

Those topics and more are taught in my Music Theory for Songwriters Course. Check out the reviews, people absolutely love the curriculum and have seen huge improvements from the course!

The Bottom Line

Songwriting isn’t a mysterious gift – it’s a skill anyone can learn. You just need to understand the rules and practice. Once you’ve got these fundamentals down, you can go crazy with your own style and make it uniquely yours.

The six diatonic chords we explored here can give you endless possibilities for creating music that sounds professional and polished. Start here, master this foundation, and watch your songwriting skills grow!